- Home

- Claire Legrand

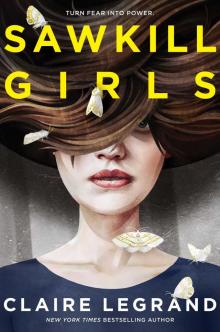

Sawkill Girls Page 2

Sawkill Girls Read online

Page 2

He reared up with a savage shudder. Marion grabbed his mane to keep from sliding off.

“Marion!” came Charlotte’s panicked shout.

But this horse would wait for no sister. It was out of its head, though Marion couldn’t imagine why. Rabies, maybe. Something had spooked it. A snake?

Nightingale bolted.

With each slam of his hooves against the hard ground, Marion imagined her father tumbling over the cliff, his head smashing against the car over and over until there was nothing left.

Zoey

The Snoop

Thora had disappeared seven months ago, and they’d never found the body.

No one had any answers other than the usual litany: you kids shouldn’t run around on the cliffs, they’re too dangerous, haven’t we told you that a million times?

Zoey had had just about enough of pretending she was okay with this.

She didn’t think, generally speaking, people were allowed to wander in off the street and go snooping around the police station like they owned the place. But Police Chief Harlow was in charge of things, so Zoey Harlow could do what she wanted to do.

It was the one paltry joy of living on Sawkill Rock alongside its army of gleaming people, with their smooth, untroubled faces and their sweat-stained riding jodhpurs and their cars that cost more than Zoey’s house.

Rosalind, sitting at the front desk, offered Zoey an oatmeal-raisin cookie and nodded at Zoey’s notebook. “What’re you writing today?”

“Haven’t decided yet!” Zoey replied. Which was true. She hadn’t decided yet since Thora died. Her half-filled notebook remained half-filled. The only thing to come out of Zoey’s pen over the past few months besides schoolwork were doodles of farting unicorns.

She rounded the corner, parked herself in the staff lounge, showed an old scrap of a poem to her father’s nosy deputy, and doodled flatulent mythological creatures for a half hour. When the place had emptied out for lunch, Zoey retrieved her dad’s office key in her pocket, crept through the quiet hallways, unlocked his door, and slipped inside.

Her heart raced. She’d been in this office hundreds of times since moving to Sawkill two years ago. But she had never entered it without her father’s permission—and definitely never with the intent to snoop.

Zoey crept around the desk, opened the six desk drawers, leafed through papers. The office was immaculate—no surprise there—but that meant she had to go slowly, make sure she put everything back exactly where she’d found it. Ed Harlow was the kind of guy who’d flip out—mostly good-naturedly—if someone misplaced a single book.

He’d told her once, The world is a crazy place, Zo. I like to keep my part of it as neat as I can.

Which was all well and good, albeit painfully dorky. Still, this wasn’t the first time Zoey had wished her dad was a slob.

Nothing in the desk. Nothing on the desk.

Zoey turned around, eyed the row of file cabinets lining the back wall—eight altogether—and blew out a sharp breath.

“Wow, Dad,” she muttered. “Got enough file cabinets?”

She opened the first one, thumbed through the hanging files. A bunch of administrative crap. Forms and forms and more forms. Useless.

Next: Three-ring binders packed with training manuals.

Next: Employee files. Performance reviews. A handwritten letter of complaint from Sergeant George Montgomery III about the hazardous levels of perfume Rosalind insisted upon wearing. Really, Chief, Sergeant Montgomery had written, I fear for my health.

Smirking, Zoey closed the third file cabinet, stretched her arms over her head, yawned.

Then she saw it. A new addition to her father’s office: a small, square picture in a silver frame, sitting in a lineup of other framed photographs on a narrow corner table. Zoey’s own brown face—skin a bit lighter than her dad’s rich brown, dusted with a few of her mother’s freckles—smiled up at herself. Her chin-length black curls framed her face like a cloud, and she had her arms thrown wide, as if to declare that the person grinning beside her was a revelation to be flaunted.

Zoey touched Thora’s image—white skin, mousy brown hair, cheeky grin, shining eyes. Zoey’s tears came so quickly that their arrival made her choke a little.

Thora.

Presumed dead at seventeen, and no one knew why, or when, or how.

Zoey closed her eyes, turned away from the frame and Thora’s giddy image. She remembered the day from the photo: Zoey’s seventeenth birthday party. Thora and Grayson were the only attendees, and the only ones Zoey had wanted to see (and the only ones who would have come to a party of Zoey’s, but whatever). A movie marathon—Alien, Aliens, then, at Thora’s request, The Breakfast Club, then, at Grayson’s request, sleep, for the love of God. It was 4:30 a.m. Thora’s voice, giggling: Grayson, you are such an old man. All of them piled on the couch in Thora’s basement. Thora snoring against Zoey’s shoulder. Grayson’s hand touching Zoey’s.

They hadn’t yet had sex, her and Grayson. And she hadn’t yet broken up with him.

And Thora hadn’t yet been murdered.

Well, and that was the thing, wasn’t it? No one thought Thora had been murdered. Not officially, anyway. There had been no evidence of murder; everyone’s alibis had checked out.

“There are wild animals on our island,” Zoey’s father had said in an interview with the mainland paper, “not to mention very dangerous areas on the cliffs where the ground can give way without warning. Please, to all our young people, and to any visitors: do not go wandering in the woods after dark.”

Wild animals. Collapsing cliffs.

Sure. Zoey guessed so.

But those were the same bullshit reasons people had been giving for Sawkill’s disappearing girls for years. Decades, even. Zoey had never bought it.

And now, with Thora gone?

Thora, who’d always understood when Zoey wanted to stay in instead of go out. Thora, who’d obsessed over fandoms even more obscure than Zoey’s. Thora, who’d always whispered the old island monster tales before bed when Zoey and Grayson slept over, even when scaredy-cat Grayson had begged her not to:

Beware of the woods and the dark, dank deep.

He’ll follow you home and won’t let you sleep.

Zoey slammed open the door of her father’s fourth file cabinet, blinking back her tears.

With Thora gone, Zoey was no longer satisfied with the non-answers of the local law enforcement. Not even when their boss was her dad.

But just as she started flipping through a new drawer of hanging files, a scream cut through the silence—a horse scream. The most terrible sound in the world.

Zoey felt like she’d stepped through a veil into winter. She kicked the cabinet door shut, then hurried to the window and squinted into the sunlight, just in time to see Nightingale, her father’s horse, rear up in the parking lot of the market next door, his front legs clawing the air. Her father fell back, hit the ground hard, but Zoey wasn’t worried. Ed Harlow was made of granite.

The reins went flying. Someone was on Nightingale’s back.

Zoey didn’t recognize her—some white girl with long dark hair.

“Marion!” Another white girl, wearing a faded red parka, rushed across the parking lot, grocery bags swinging from her hands.

But it was too late.

Nightingale surged through the rows of parked cars. His coat glistened with sweat.

The girl on his back held on for dear life, hair streaming behind her. It was painfully obvious that she wasn’t a Sawkill girl.

One, her clothes looked secondhand, like Zoey’s—except they lacked what Zoey liked to refer to as her middle-finger flair. Artful rips, plain fabric dyed in shocking colors, wild fringe where there had previously only been a plain, uninteresting hem.

And two, the girl couldn’t ride for shit.

Zoey sympathized. Her first and only riding experience had ended with a full-blown panic attack on the back of a sedate whiskered police horse wit

h woebegone eyes.

“Jesus,” Zoey spat.

She sprinted down the hall and outside, grabbed her mud-splattered mountain bike from where she’d left it hidden behind the hedge, and took off pedaling.

Nightingale was taking the Runaround Road, pebbled and dusty white. It circled the outskirts of town, along the Black Cliffs that capped the hilly shoreline of the island’s western face, and eventually sloped down into the Spinney.

It was a road meant for pleasant seaside strolls, not for panicked horses on a tear. Nightingale would fall, break his leg, throw the girl. If she was lucky, she’d hit a bush beside the trail.

If she wasn’t lucky, she’d land on the black sea rocks below the cliffs.

Zoey pumped her legs as hard as she could. From behind her came the wail of her father’s patrol car, the pounding of feet as people ran after them down the road.

“Come on, come on,” she muttered, glaring through the wind at Nightingale’s racing dark form. “Calm down, you stupid horse.”

At Runaround Road’s highest point, Nightingale let out another one of those awful, bloodcurdling screams and disappeared over the other side.

Shit, shit, shit.

Zoey’s muscles burned as she pedaled up the slope, and then she was cresting the hill and flying down the other side. Runaround Road ended in a tiny tree-ringed overlook that Val Mortimer had long ago claimed as her favorite hookup spot.

There, in the center of what Zoey had coined the Viper’s Den, the girl lay unmoving in the dirt.

Nightingale tore off into the trees, reins trailing.

“Damn it,” Zoey muttered, braking hard. She sprinted to where the girl lay with her eyes closed, checked for blood.

No blood.

Breathing?

She checked her pulse.

Yes, breathing.

Zoey smoothed back the damp hair clinging to the girl’s forehead.

“Hey,” she murmured, cupping the girl’s right cheek with her right hand. “Can you hear me?”

Over the years, Zoey had remade herself from the kind of girl who cried when she saw roadkill to the kind of girl who shoved down her tears so deeply it sometimes felt she’d forgotten how to cry at all. Things were easier that way.

But now, kneeling in the chalky white dirt beside this girl, Zoey felt her eyes well up for the second time in ten minutes.

“Look, you’ve got to open your eyes,” she said, “because I could use another secondhand girl around here. You know what I’m saying?”

“Zoey? She all right?” Her father was running down the hill, shouting into his phone. “Yeah, we’re at the White Rock Overlook. No, I can’t tell yet.”

“Marion?” More footsteps racing down the hill, lighter ones. “Marion! I’m coming!”

“Is that your name?” Zoey leaned closer. “Hey. Marion? I’m Zoey. You’re gonna be okay.”

The girl from the parking lot, wearing the red parka, knelt beside Marion with tears in her eyes.

Zoey, afraid to move Marion, kept the girl’s face in her hands. If she woke up, she’d feel the comfort of warm skin on her face and know she wasn’t dead.

“Hush now,” came another voice, light and feminine. “I’ve got you.”

Zoey froze at the sound of that voice. She knew it well, and she was sorry she did.

At the edge of Zoey’s vision stretched a pale hand with shining manicured nails, trimmed short.

Parka Girl took the hand and rose.

“She’s not moving,” said Parka Girl, voice thick with tears.

“She’ll be all right,” answered Val Mortimer, in that voice that wasn’t fooling anyone, and yet it did in fact seem to fool everyone. It had even fooled Thora.

It did not fool Zoey.

Zoey concentrated on Marion’s unconscious face so she didn’t have to listen too closely to Val and Parka Girl talking. But she did catch some things: The girl’s name was Charlotte. She was Marion’s sister.

Their father had recently died.

“Don’t worry,” Val reassured Charlotte. “Chief Harlow always knows just what to do.”

Zoey couldn’t help it. She glared back at Val. Bitch bitch bitch.

Val had her arms around Marion’s sister. Her smile was made of diamonds and beestings, and she flashed it at Zoey as if to say, Go ahead. I dare you.

And to think that after Thora died, Zoey had actually considered reaching out to Val:

She was my friend, too.

At least, she used to be.

It was at that moment that Marion’s bloodshot eyes snapped open.

And she began screaming.

Val

The Viper

Val ignored Nightingale and the girl clinging to his back.

Instead, she watched the girl running after them.

This second girl wore a red parka, and though she ran alongside the crowd of gaping, shouting shoppers, she somehow existed apart from them. There was a sharp shine to her pink cheeks. The fragility of her fearsome, fearful girl-body made Val’s chest ache, and electrified the fine hairs on the back of Val’s neck, and awoke Val’s deep-gut appetite that belonged to herself, a little, but mostly belonged to him.

A force pulled at Val’s flat belly. She took a step against her will.

He had noticed. He’d sensed the girl, and Val didn’t want to follow her, but he wanted her to, and that was that.

Or was it?

Was it really?

Val, feeling bold, decided to test him. Her grandmother had warned her against defying him too often, but she had also warned Val against never defying him.

Don’t lose yourself to him, my darling one, Sylvia Mortimer had said. Not all of you.

Keep a morsel for yourself.

Val closed her eyes, remembering her grandmother’s words: That’s what the first of us said—your great-great-great-grandmother Deirdre. She told her daughter, and so on, until my mother told me, and I told Lucy, and now I’m telling you, because your mother . . . Well. She’s harder than the rest of us. She’s had to become that way, because it’s hurt her more than anyone else. He’s hurt her more than anyone else, and now there’s nothing left of my daughter but a brittle shell.

So just listen to me, Valerie: keep a morsel for yourself. Whatever happens, hold that scrap tight.

A bramble took root in Val’s stubborn feet. Maybe if she stood there long enough, briar tangles would wrap her up within an enchanted wall, and the wall would stand guard around the sleeping girl until the prince came and burned everything down.

That’s how the story went, right?

Go.

Val’s spine snapped to attention, all hungry teeth and whetted knives and manacled rows of bones. Her mouth dropped open and tears sprang to her eyes. He hardly ever spoke to her directly. Not in parking lots. Not under the open sky.

She’d pay for her hesitation, later, in the stones.

Val ran, sprinting ahead of the crowd, and she looked good doing it, in her second-skin yoga pants, her blond hair piled on top of her head. Of course she looked good, everyone knew it—her most of all. She’d spent a lifetime maneuvering all manner of things to make it so.

Plus, good genes. She’d been blessed with stellar DNA.

“Make it stop!”

The girl on the ground—Marion was her name—screamed the words over and over, thrashing against the rocks. She gripped her hair, her head, she wept and wailed.

Zoey Harlow swore, jumped to her feet, and backed away.

For once in her life, Val agreed with the little shit.

“Marion?” Parka Girl, the girl he wanted, rushed to Marion, her pale face gone ghostly. Her name was Charlotte Althouse, and she was the daughter of the new housekeeper, and Val wanted to throw back her head and laugh because this situation was unfolding so perfectly it almost couldn’t be believed.

“What’s happening?” Charlotte cried. She reached for Marion, but Marion slapped her hand away.

A siren’s wail. Chief Har

low to the rescue, straddling Marion and pinning her arms to the dirt in a way that made Val’s mouth fill with bile and her limbs go hot-cold. She didn’t like seeing people trapped. Not strangers, not friends, not even the hateful boys she slept with.

Valerie Mortimer’s nightmares were of being pressed into a shrinking space that compressed all her disjointed parts into an invisible cage. She endured them every night.

“Marion?” said Chief Harlow, in that booming voice like a deep canyon. “You’re all right. You’re all right, help is coming. Okay?” His eyes flicked up to Zoey. “Did you see what happened?”

“No.” Zoey crossed her arms over her chest and chewed on her thumbnail. Her Afro of soft black curls, recently peppered with bright orange streaks, bobbed slightly in the sea wind. “Came over the hill, Nightingale was gone. She was just lying here.”

People were crowding around, finally having caught up with them. Their sweat sickened Val. All these dirty flesh-bags, acting like they were something, with their horse farms and their tricked-out sedans, their portfolios and their trust funds, when it was her, it was her who had the power here, who knew more than they could ever fathom. How dare they inch up close like they were all in this together?

She whirled around. “Back up,” she ordered, in the voice her mother had taught her—one part sweet, two parts you’d-better-damn-well-listen-to-me. “Give them some air. And put away your phones. Have you all forgotten how to be human beings?”

Her latest conquest, Collin Hawthorne, hovered nearby. He watched her in a sort of stupid half-smiling daze.

Val recognized that awestruck look and imagined how it would transform, were he to stumble upon her in the stones one night. She almost wished he would, even though it would get messy. Just to see him, for that final flash of a second, understand exactly what he’d been sleeping with.

“People!” he called out, mimicking her, which Val found hysterical. “Back up, all right? Let the paramedics work.”

Furyborn

Furyborn Queen of the Blazing Throne

Queen of the Blazing Throne Lightbringer

Lightbringer Kingsbane

Kingsbane Cavendish Home for Boys and Girls

Cavendish Home for Boys and Girls The Year of Shadows

The Year of Shadows Some Kind of Happiness

Some Kind of Happiness The Cavendish Home for Boys and Girls

The Cavendish Home for Boys and Girls Sawkill Girls

Sawkill Girls Foxheart

Foxheart Summerfall: A Winterspell Novella

Summerfall: A Winterspell Novella