- Home

- Claire Legrand

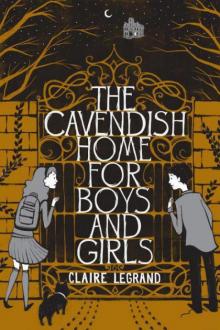

The Cavendish Home for Boys and Girls Page 5

The Cavendish Home for Boys and Girls Read online

Page 5

Someone knocked on the door. Victoria quickly cleaned her face with a blanket and smoothed her wrinkled uniform flat. She smiled brightly at the door.

“Yes?” she said.

“I’ve got your snack” came Beatrice’s voice.

Victoria hesitated. She hadn’t forgotten the little slip of paper Beatrice had left under her breakfast plate, days ago: Be careful. The memory sat strangely in her body after the events of the past week. Before, she hadn’t cared about Beatrice’s odd note; but that was before, and now she found herself wondering . . .

“Come in,” she said, tugging her shirt straight and tossing back her curls.

Beatrice brought in a tray with cut-up fruits laid out in a row—tomato slices, apple wedges, strawberry halves. She shut the door and put the tray on Victoria’s bedside table, chattering about her day.

“I picked up your new tights for ballet tomorrow. I think you’ll like the penne with salmon I’m cooking for supper tonight. Did you have a good day at school?” said Beatrice, on and on, dusting off surfaces that didn’t need dusting. Between Beatrice and Victoria, this room was always the cleanest in the house.

Victoria watched her but didn’t really pay attention. She chewed on a tomato slice. The skin tore and the meat melted on her tongue. As she chewed, she mulled over things: Professor Carroll and Professor Alban; Donovan O’Flaherty and Jacqueline Hennessey being absent for days; Mr. Alice and his rake; Beatrice’s note; Jill saying, “Be careful, Victoria.” Separately, they were little things; but put all together, they seemed somehow more.

“What did you mean by that note the other day?” Victoria said.

Beatrice froze. “Note?”

“The note that said, ‘Be careful.’ What does that mean? Be careful of what?”

“I’m not sure what you mean,” said Beatrice. Then she knelt in front of Victoria and whispered, “I can’t say too much. I don’t want anything to hear.”

Victoria said, “Anything? You mean you don’t want Mother and Father to hear? Why not?”

Beatrice wiped her hands on her apron. It was the latest in housekeeperly fashion. Mrs. Wright made sure of it.

“Just go on about your business,” Beatrice said, looking around the room as though she expected someone to be there listening. “If we’re lucky, everything will soon be back to normal. Sometimes it’s worse than others, you see. Like the weather.” Beatrice shook her head. “But you just have to pretend like nothing is happening.”

“But what is happening?” Victoria said. “Something is, isn’t it? The teachers at school are acting weird. And Lawrence—” She stopped, swallowing hard. “Lawrence is gone.”

“He’s not gone,” said Beatrice. “He’s visiting his grandmother upstate.” She didn’t sound like she believed her own words.

“Fine,” Victoria said. “I don’t believe you, but fine.”

“You have to believe me,” said Beatrice. “If you start misbehaving—” She cupped Victoria’s cheek. Her mouth trembled, making her look ancient and exhausted. Then her eyes went a little fuzzy, like something had wiped them blank. “I . . . I don’t . . .” She shook her head. When she opened her eyes again, they still had that blurry look about them. “Just do as you’re told. Please?”

Inside, Victoria’s heart hardened suspiciously into its own version of a dazzle. Outside, Victoria smiled and had a strawberry.

“I will,” she said, and after Beatrice left, Victoria paced her room for a long time and finally stopped at the window to look outside.

Mr. Tibbalt’s dog bounced at the corner of the street, yapping down Bourdon’s Landing, Lawrence’s street. Something about the sight of him stabbed Victoria with a jolt of dread. For some reason, deep down in her stomach, she knew she had to follow him.

Victoria grabbed her coat and snuck downstairs. She almost made it outside, but then her mother called out, “Victoria? Where are you going?”

“Um,” said Victoria. She wasn’t used to lying. Lying meant secrets and things all out of order and possibly getting into trouble.

Beatrice looked at her from the kitchen and shook her head frantically, but Victoria ignored her.

“Mr. Tibbalt’s dog got out, Mother,” said Victoria. “I’m going to take him back.”

“Mr. Tibbalt?” said Mrs. Wright, her voice angry, but Victoria was already outside and didn’t hear.

She wanted to run but made herself walk instead, Victoria-style—with purpose, briskly, as if people weren’t in fact going crazy all around her. She didn’t know why it was so important to act normal, but she knew that it was. Walking instead of running, like she wanted to, made her skin feel like it would burst open.

When she reached Mr. Tibbalt’s dog, he stopped yapping and looked up at her. His tail wagged uncertainly.

Victoria wasn’t used to talking with animals. “Well?”

The dog tilted his head.

“I don’t know what I’m doing out here,” said Victoria, looking around. The intersection pulsed with the oncoming storm—or was it going rather than coming, or had it always been there, stewing? In the yellow-green light, the cobbled streets shone. The air smelled bitter and sharp-sweet, like rotten food. Victoria’s heart pounded. “I should be inside doing my exercises, but I’ve got such a weird feeling all the time now. Like something’s not quite right.”

The dog sat down. His shiny black nose twitched.

“You’re no help at all,” said Victoria.

The dog got up and walked a little ways down Bourdon’s Landing, stopped in front of Lawrence’s house, sat down, and looked back at Victoria.

Victoria’s skin prickled, and she headed toward him. When she passed him, he didn’t get up to follow her.

“Aren’t you coming?” she said.

The dog’s ears perked, but he stayed put. He panted in the direction of the Prewitts’ house.

“What? Why are you doing that?”

The dog whined. Victoria followed his gaze through the gate to the Prewitts’ front door. They would be home by now; their dental practice closed early on Fridays. She squared her shoulders, tossed her curls, and opened the front gate.

“Don’t be stupid,” she muttered to herself. “The dog’s only a stupid dog, and you’re only going to peek in and make sure everything’s all right, simple as that.” She followed the damp stone walk and picked up the cold brass knocker. She knocked so many times, she thought the Prewitts’ neighbors might call the police, but no one opened the door. All the blinds were shut.

“That’s odd,” said Victoria. She went around to the side of the house and leaned off the porch but saw nothing except one dim light in an upstairs window—and in the window, a person watching her.

Victoria’s mouth turned dry. It’s only Mr. or Mrs. Prewitt, she told herself. A brush of wind against Victoria’s hand pulled her back around the corner of the house. When she tried to put her hands in her pockets and walk away, she realized it hadn’t been wind at all.

It was a roach, glossy and black with long feelers, sitting on the back of her hand and clicking glossy black eyes at her.

Victoria screamed and flung it away.

The roach or beetle or whatever it was landed on its back with a wet smack and waved its legs around to turn itself over. It scuttled off into the garden.

Victoria wiped her hand on her coat to clean off bug germs and hissed when something stung. She looked down and saw ten little red marks in her skin where the bug’s legs had been.

“Ow,” she whispered. She tried to remember everything she knew about roaches and beetles, which wasn’t a lot. But surely their feet weren’t supposed to cut you like that. And didn’t they only have six legs?

“Evil bug,” she said. Then, she thought, How strange, because as much as she didn’t want to think about it, this bug’s feelers had looked an awful lot like the feelers poking around on Professor Carroll’s desk. She shuddered to remember that. Was Belleville under attack by some sort of roach infestation? But

how could it be? Belleville was the cleanest, loveliest town around.

Gritting her teeth, Victoria said, “I . . . hate . . . nonsense,” and marched back to the Prewitts’ front door and prepared to knock again, angrier this time—but the door was already open a crack.

Victoria pushed it open the rest of the way and stepped inside. She left it open in case she needed to make a quick exit. The fact that she had to think about things like quick exits infuriated her.

“I just want things to be normal again,” she said, to herself and to anyone who might be listening. She took a few steps and stopped.

Music. Specifically, piano music.

Her heart lifted, and she didn’t care that it was silly, being so happy to see Lawrence again. She grinned and ran for the lounge, but when she got there, the piano stood closed. The music wasn’t coming from the piano, which already looked gray with dust, like no one had touched it for years.

Victoria turned to find the source of the music and almost screamed.

Mrs. Prewitt sat in the high-backed chair across the room, holding a bowl and spoon in her hands once more, stirring and stirring. Flies buzzed around whatever sat in the bowl. Mrs. Prewitt stared at the piano and swayed along with the music, which Victoria realized was coming from a radio on top of the piano, and not the piano itself.

“Isn’t it lovely?” said Mrs. Prewitt, smiling that same too-bright smile, although now it seemed strained, like she was too tired to smile but had no choice in the matter.

Victoria listened and recognized the music at last—a Chopin nocturne, one of Lawrence’s favorites. E-flat major, opus 9, number 2. She could almost picture his dreamily smiling face as he said how playing it made him feel like he was floating.

Fists clenched, Victoria said, “Yes. It’s beautiful.”

Mrs. Prewitt nodded, staring at the silent piano. “One of his favorites.”

Victoria’s eyes narrowed. “One of whose favorites?”

“Lawrence’s.”

“I miss him,” said a new voice—Mr. Prewitt, who stood silently in the shadows at the top of the stairs.

Victoria backed away, right into the piano. “Mr. Prewitt, I didn’t see you there.”

“Yes,” said Mrs. Prewitt, nodding. “We do miss him. But he’ll be back.” She turned slowly to face Victoria, plucked a stinking ball of something from her bowl, and took a crunchy bite. “He’ll be back before you know it.”

“I, er, I have to go,” Victoria breathed, stumbling back toward the door.

“Oh, stay a while,” said Mr. Prewitt, walking slowly down the stairs. He smiled and put out his hand. “You can stay with us and have supper.”

“No, really, it’s all right, thank you,” Victoria said, and she turned and ran and didn’t stop till she was safely down the walk. Looking back over her shoulder, she saw nothing but an empty black street with lamps blinking awake.

Mr. Tibbalt’s dog met her at the corner where she’d left him. His fur stood up straight in a growling red poof. He started following her, his claws clicking on the walk.

“I’m going to find out exactly what is going on here,” Victoria said, her voice shaking, the image of the Prewitts’ tight, frozen, perfect faces making her heart race. The rotten smell from Mrs. Prewitt’s bowl filled her nose and mouth. “I’ll knock on every single door if I have to.” She turned the corner and pressed the buzzer on Two Silldie Place’s gate.

Mr. Everett answered. He and Mrs. Everett were very old and collected porcelain figurines of African animals.

“Yes?” said Mr. Everett, through the intercom.

“Mr. Everett, it’s Victoria. May I come in, please?”

“Virginia?”

“No. Victoria.”

“What now?” said Mr. Everett.

Victoria heard Mrs. Everett sigh and say, “It’s Victoria, darling,” and the gate clicked and started opening. “Victoria Wright.”

Mr. and Mrs. Everett let Victoria in and gave her tea, which Victoria only pretended to sip at.

“Have you seen my latest giraffe?” said Mrs. Everett, and she held out a giraffe with a neck twice as long as its stub of a body, painted in pinks and blues. “It cost one thousand dollars. It’s an antique, you know.”

All the Everetts’ figurines were antiques. Victoria couldn’t believe something so ugly was so expensive. She also couldn’t believe that a pink and blue giraffe was an antique.

“Yes, it’s nice,” said Victoria. “Now I have a question.”

“Why, ask away!” said Mr. Everett, looking over their shelves for another figurine to show off. His hand was reaching for a smiling crocodile when Victoria said, “It’s about the Prewitts.”

The Everetts paused. They looked at each other and then at Victoria. They didn’t say a word. Mrs. Everett poured Victoria more tea and dumped four spoonfuls of sugar into it.

“The Prewitts,” Victoria said. “You know.”

“Yes, of course,” said Mrs. Everett.

“Are they sick or something? Do you know? And Lawrence—”

“He’s out of town,” said Mr. Everett. “Visiting his grandmother. That’s what we heard.”

“That’s right,” said Mrs. Everett. “We did hear that, didn’t we? Just the other day.”

Victoria said, “Yes, yes. But—” She paused. “Did you hear when he’ll be back?”

The Everetts looked at each other again. Mrs. Everett held out her giraffe and smiled. “But don’t you want to see the rest of our collection?”

“Look at this croc,” said Mr. Everett, his pointy white teeth matching the crocodile’s grin. “Priceless, you know. We have only the best in our collection.”

Oh, they knew something, all right. Victoria could see it with her dazzle eyes. They were only pretending they didn’t know what she was talking about. They weren’t going to help her. This realization enraged her. She forced herself to smile the sweetest smile she had ever worn.

“I’m so sorry, but I have to go,” she said at last, stopping just short of slamming down her teacup. “Thank you ever so much for your time.”

She tried next door at Four Silldie Place, but no one answered, even though Victoria could see shapes watching her from the upstairs windows.

“Well, what about your Mr. Tibbalt?” she said to the dog, who still followed her. The gate to Six Silldie Place stood just open enough for Victoria to slip inside. The dog ran after her to the front door.

“What do you want?” someone growled.

Victoria stopped just before the porch. Mr. Tibbalt stood at the front door with his dog in his arms. The dog seemed perfectly happy, but Mr. Tibbalt did not. He frowned down at Victoria from beneath a rumpled wool cap. It was as patched and worn as the rest of his clothes. His glasses glinted in the lamplight, blocking out his eyes.

“Excuse me, Mr. Tibbalt,” said Victoria, hiding her disgust at his messy clothes and the awful state of his lawn. Her mother’s red notices flapped all along his porch. “I hate to bother you, but I have a question.”

“No more questions,” muttered Mr. Tibbalt. “Too many questions.”

Victoria couldn’t believe his nerve.

“It’s about the Prewitts,” she persisted.

For an instant, Mr. Tibbalt straightened and came alive. He said something Victoria couldn’t quite hear, except for one word: “Vivian . . .”

The wind slammed the gate open. Mr. Tibbalt jumped and waved his arm at Victoria. “No more questions,” he cried. “Get out of here. Go away!”

Victoria scoffed, glaring at his messy clothes. She should never have bothered with this crazy old man. “I will, but not because you told me to.” She turned and left, ignoring the dog’s indignant yaps.

“Why, Victoria, how nice to see you,” said Mrs. Baker at Eight Silldie Place. She was young and pretty and held her new baby. Her small, pretty children ran in circles behind her.

“Victoria,” said handsome Mr. Baker, wiping his hands on a towel. “We just made supper. Woul

d you like to join us?”

“No, thank you,” said Victoria, still so furious at Mr. Tibbalt that she didn’t bother with small talk. “I’ve come to ask you about the Prewitts and what’s wrong with them and what they’ve done with Lawrence.”

The Bakers stopped moving. Their smiles froze in place.

“What they’ve done with him?” said Mr. Baker, suddenly much cheerier than a moment ago.

“Something’s wrong, I know it is,” said Victoria. “And no one will tell me.”

Mrs. Baker chuckled. “Sounds like the storm’s giving you crazy ideas, Victoria.”

“I don’t get crazy ideas.”

“Well,” said Mr. Baker, his smile widening. His and Mrs. Baker’s heads tilted strangely, as though they were birds. “I think you should go home now, Victoria.”

They tried to lead her out the door, but Victoria dug in her heels. “But wait! I want to stay and eat supper with you after all.”

“Oh, I’m sorry, Victoria,” said Mrs. Baker. “It’s getting so late, you see.” Together, the Bakers pushed Victoria out, shut the door, and locked it.

Victoria stood alone on the porch, the wind whipping her hair around. Her curls were falling out, which added insult to injury.

“Fine,” she said. Clearly, everyone around here knew more about what was going on than they were telling her, and nothing about any of it made any sense. And things were supposed to make sense in Belleville. The entire situation was unacceptable.

“So rude,” Victoria said, straightening her coat with a snap. “Maybe Mrs. Cavendish will be more polite.” She walked to the end of the street, stopping right at the Home’s gate. The gray brick wall disappeared into the woods on either side. There wasn’t a buzzer or anything.

Furyborn

Furyborn Queen of the Blazing Throne

Queen of the Blazing Throne Lightbringer

Lightbringer Kingsbane

Kingsbane Cavendish Home for Boys and Girls

Cavendish Home for Boys and Girls The Year of Shadows

The Year of Shadows Some Kind of Happiness

Some Kind of Happiness The Cavendish Home for Boys and Girls

The Cavendish Home for Boys and Girls Sawkill Girls

Sawkill Girls Foxheart

Foxheart Summerfall: A Winterspell Novella

Summerfall: A Winterspell Novella